Series: Open Knowledge Fellowship 2025

The homegrown record label, ‘Young India’ shaped the subcontinent’s sound recording industry at a pivotal moment in cultural history. Recording technology transformed the once-ephemeral nature of sound into tangible discs. Sound, in all its forms, textures, and cultural significance could now travel tangibly. Each disc became a vessel of its time carrying language, identity, and political sentiment across distances.

I first came across the Young India label while reading Andrew Einsenberg’s article “The Swahili Art of Indian Taarab”. The idea that an Indian record label influenced sonic traditions across the Indian ocean, intrigued me. The label was as a cultural force, pressing voices from a nation on the cusp of independence into permanence. Political speeches, music, dramas, and devotional songs were recorded in diverse regional languages. This had a significant influence not only in India but also across the Indian ocean.

But how had a homegrown record label from colonial India, with such influence, faded from public memory?

By the early 1900s, the sound recording industry in India was thriving. But European labels such as Beka, Columbia, Odeon, Pathé, His Master’s Voice dominated the market. These British, German and French companies recorded Indian regional music and musicians and sold them back to Indian audiences. Soon, Indian businessmen too entered this trade; early labels included RAM-A-PHONE by T.S. Ramachandra & Bros and Singer Record by Wellington Cycle & Co. run by Rustomjee Dorabjee Wellington and aided by T. Dorabjee and R. Dorabjee.

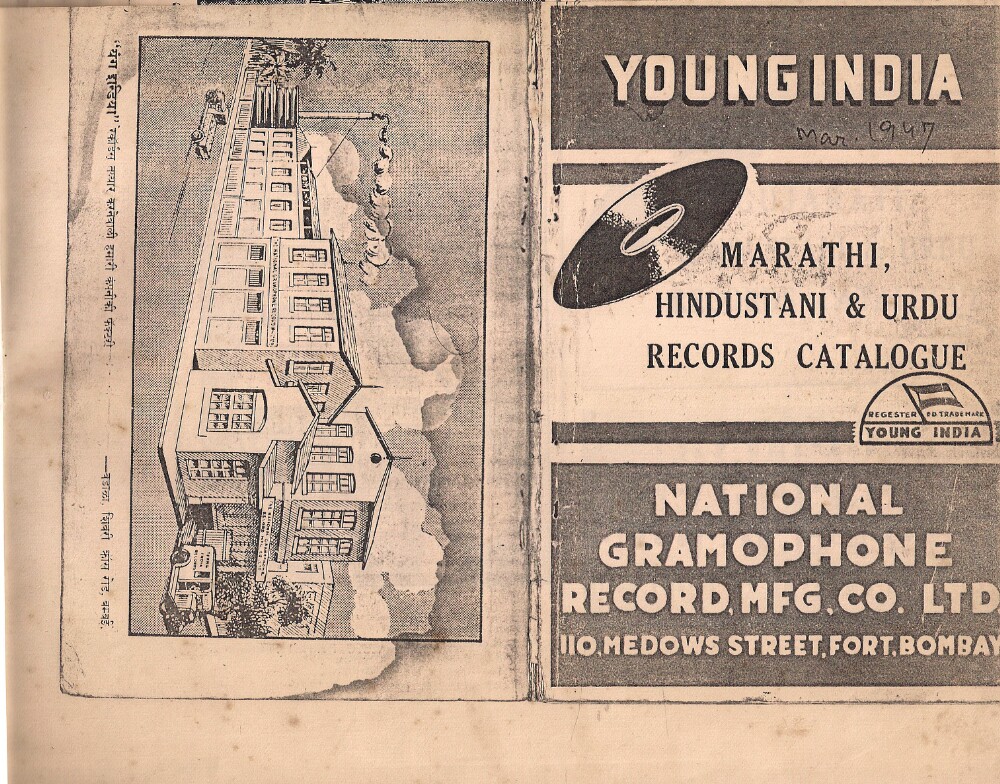

In 1934, amid the clamour of spinning records and rising nationalist sentiment, Duleria A.Pandya (and others) established The National Gramophone Record Manufacturing Company Ltd. in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay).1 The company set up a record pressing factory at the erstwhile Sri Laxmi Mills – situated at Sewri Cross Roads in Wadala. Under the company, the Young India label2 produced hundreds of 78-rpm shellac discs joining indigenous ventures in a market long dominated by European companies.

What distinguished this label from its competitors, is that it supported and encouraged emerging talent, created a partnership with Prabhat films and pressed political speeches. The label’s independence meant that it could respond to local tastes, regional languages, and national sentiments in ways that foreign labels did not.

The Young India label: a Symphony of Genres and Geographies

Young India’s catalogue reflected the diverse soundscape of Indian society in its political, cultural, and artistic flux. It encompassed devotional songs, classical ragas, film soundtracks, dramas, comic skits, patriotic speeches, instrumental music and folk music in various regional languages.

Here, we hear Jyotsna Keshav Bhole singing two Marathi songs from Aashirward – a musical drama.

The label featured notable singers such as Jyotsna Keshav Bhole, a Marathi theatre actress and a Hindustani classical musician; Firoz Dastur, an Indian actor and vocalist from the Kirana Gharana tradition; Vasant Desai, a reputed film composer and many others.

Interestingly, it also pressed speeches by national leaders such as Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose – whether these recordings were commercial releases or political parties’ outreach, remains uncertain.

Young India’s records pressed in limited quantities, make these records notable for collection. The duration of each shellac disc was around 3 minutes and pressed on both sides of the disc. The price of each record would vary according to the label colours ranging from 1 Rupee and 80 paise to 2 Rupees and 80 paise. The label also published catalogues that included the lyrics of the songs, transcription of the plays, brief description of the artists along with their photographs. These catalogues, printed in regional scripts and languages such as Urdu, Gujarati, Marathi and Hindi, ensured broader accessibility and cultural resonance.

The diversity and breadth of the label’s catalogue truly feels like it captured the essence of its time.

Young India: Bridging film and music, across geographies

The label also pressed music for Hindi films such as Nagin, Yasmin, Uran Khatola, Anarkali. One of its most impactful collaborations was with the Prabhat Film Company3; this synergy amplified the reach of both mediums, and songs from films like Sant Tukaram and Amar Jyoti became auditory icons of India’s independence era.

The label’s reach, though, extended beyond India. It recorded popular Hindi film tunes sung in Swahili by Indians who had migrated to Kenya! Song lyrics from films like Aah and Rangeela were translated and sung in Swahili.

Here is a recording of songs in Swahili sung by Sheela, Pardesi and Manorma pressed on Young India label. However, there is no information if these songs composed by Fateh Ali were original compositions or a translated renditions from Hindi films.

The movement of people, culture and recorded music through the Indian ocean led to a unique musical style. The influence of Hindi films and music in Swahili-language of Hindi films contrafacta produced by the Young India label had a ripple effect on Kenya’s coastal taraab music. The resulting sub-genre called ‘taraab ya kihindi‘ or ‘Indian taraab’, blended Swahili song lyrics with the tunes of Hindi film songs. These were performed in a unique Indian style by Kenyan taraab singers.

The National Gramophone Record Manufacturing Company also pressed records for international labels

Being a port city and place for technological advancement, Mumbai had become a hub for international record production. As a result, the National Gramophone Record Manufacturing Company’s technical and commercial reach soon extended beyond the nation. It pressed discs for labels in South Africa, Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain. Its clientele included Bahrain’s Oneon and Salimphone labels, and Iran’s Young Iran and Nava-Ye-Iran labels. I find it quite a commendable feat that this Indian record manufacturing company that once competed with European record companies, now made a name for itself at a global level.

Despite its success, the company faced financial and technical difficulties by 1948, leading to the Wadala-based factory’s eventual closure in 1955. Remaining stock was sold at subsidized prices to various agencies, marking the end of an era for one of India’s pioneering independent record labels.

Uncovering the legacy of ‘Young India’

Although Spotify’s mood-based playlists or Youtube’s algorithmic music recommendation dominates how we consume music, a simmering shift amongst younger generations in India points to a desire to engage and experience music more tactically. Physical forms- whether it is records, cassettes or CDs – offer so much more context through the liner notes, album art and appreciation for all the music personnel that brought the album to life.

Record collectors such as Suresh Chandvankar, Narayan Mulani, Michael Kinnear have collected and preserved these oft-forgotten shellac discs that carry our sonic histories. Through their digital archives and contributions to The Journal of the Society of Indian Record Collectors, the process of exploring Young India has transformed into a journey of unfolding the label as a case study in bold, values-driven publishing, intertwining culture, commerce, and community.