Charles Darwin’s work on heredity was partly driven by tragic losses in his own family. Darwin had married his first cousin, Emma, and “wondered if his close genetic relation to his wife had had an ill impact on his children’s health, three (of 10) of whom died before the age of 11,” Katherine Harmon writes at Scientific American. (His suspicions, researchers surmise, may have been correct.) He was so concerned about the issue that, in 1870, he pressured the government to include questions about inbreeding on the census (they refused).

Darwin’s children would serve as subjects of scientific observation. His notebooks, says Alison Pearn of the Darwin Correspondence Project at Cambridge University Library, show a curious father “prodding and poking his young infant,” Charles Erasmus, his first child, “like he’s another ape.” Comparisons of his children’s development with that of orangutans helped him refine ideas in On the Origin of Species, which he completed as he raised his family at their house in rural Kent, and inspired later ideas in Descent of Man.

But as they grew, the Darwin children became far more than scientific curiosities. They became their father’s assistants and apprentices. “It’s really an enviable family life,” Pearn tells the BBC. “The science was everywhere. Darwin just used anything that came to hand, all the way from his children right through to anything in his household, the plants in the kitchen garden.” Steeped in scientific investigation from birth, it’s little wonder so many of the Darwins became accomplished scientists themselves.

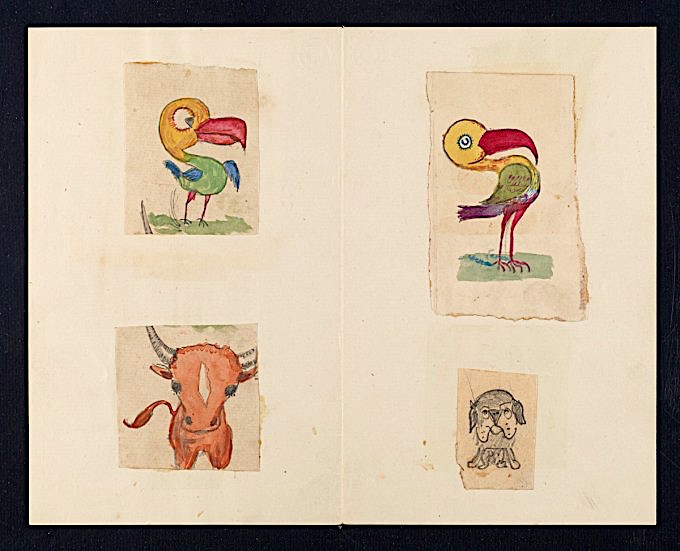

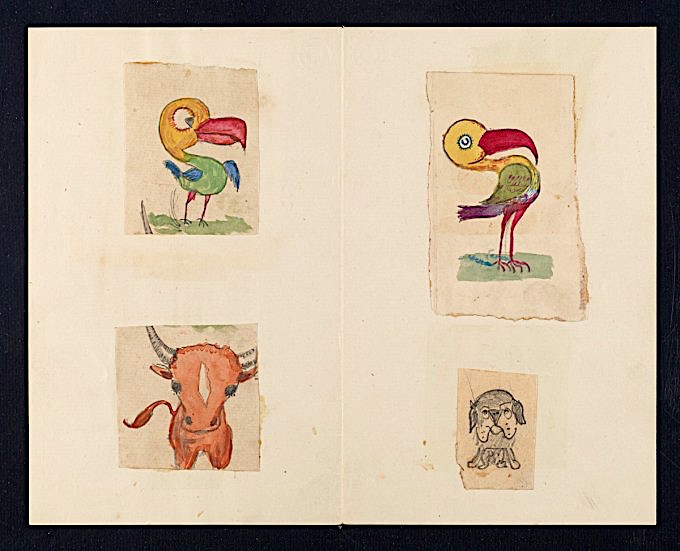

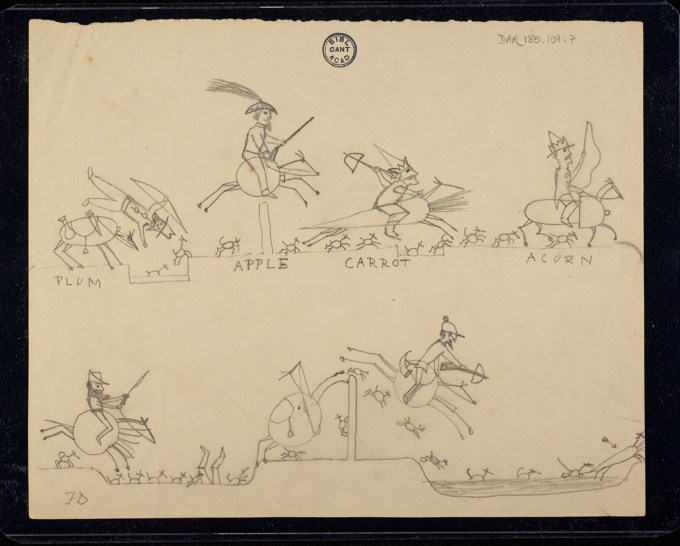

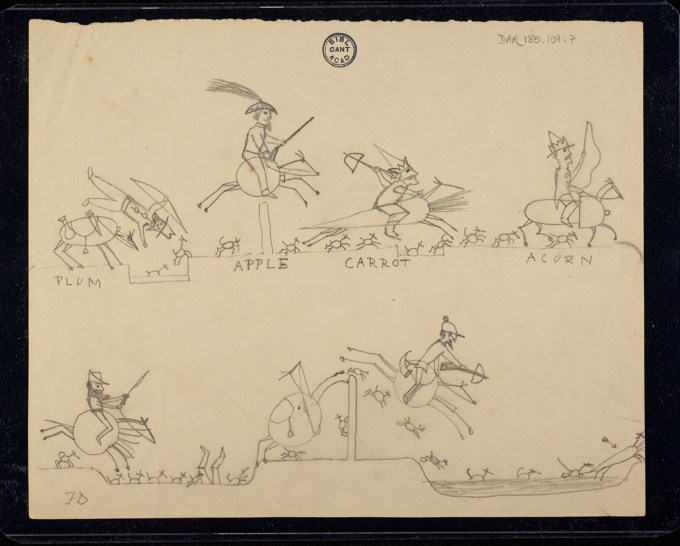

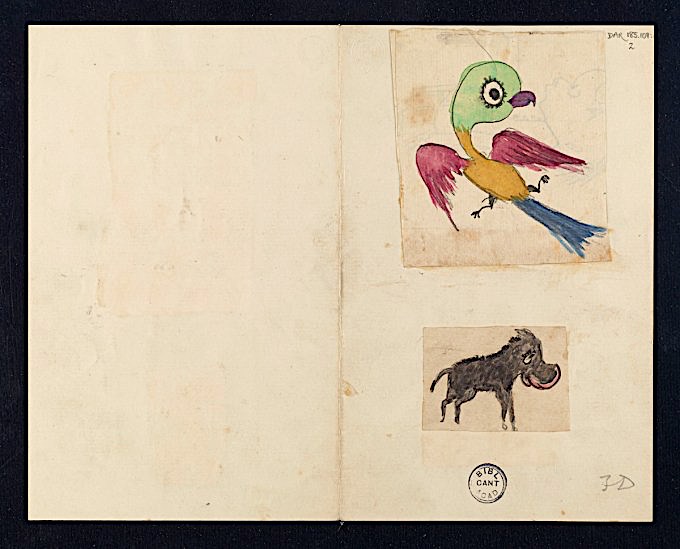

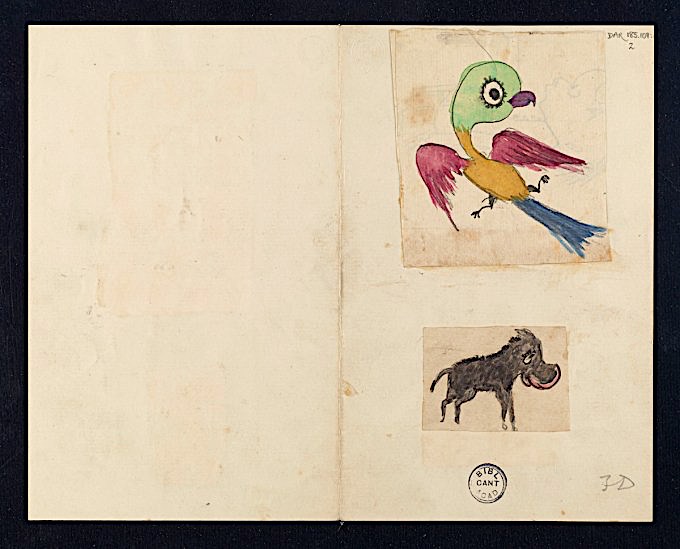

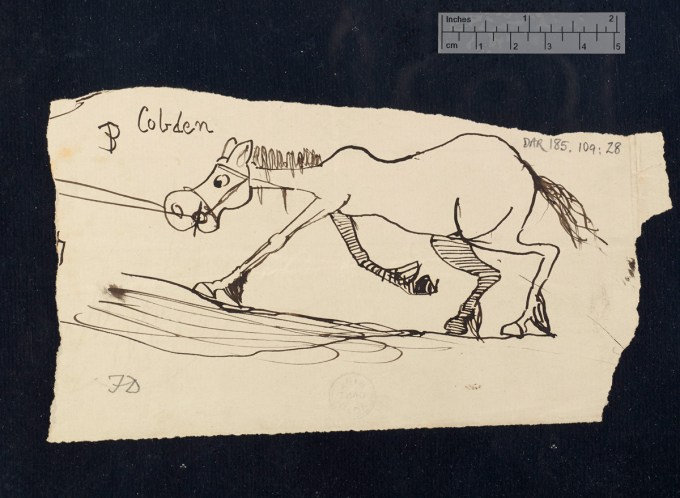

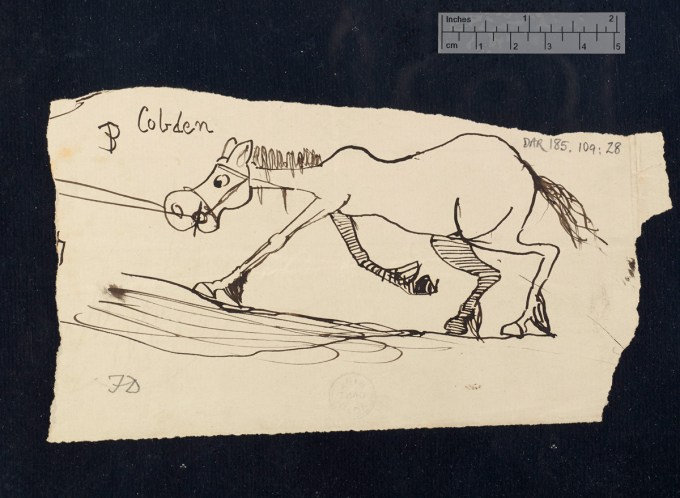

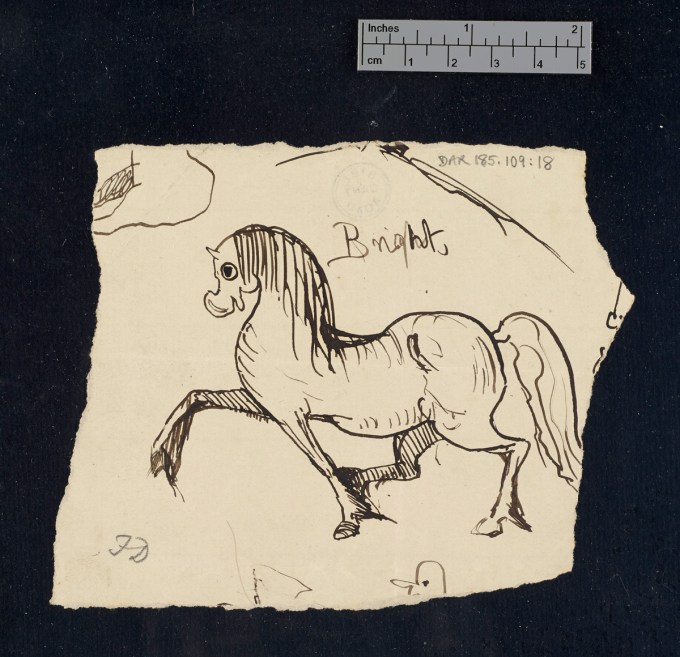

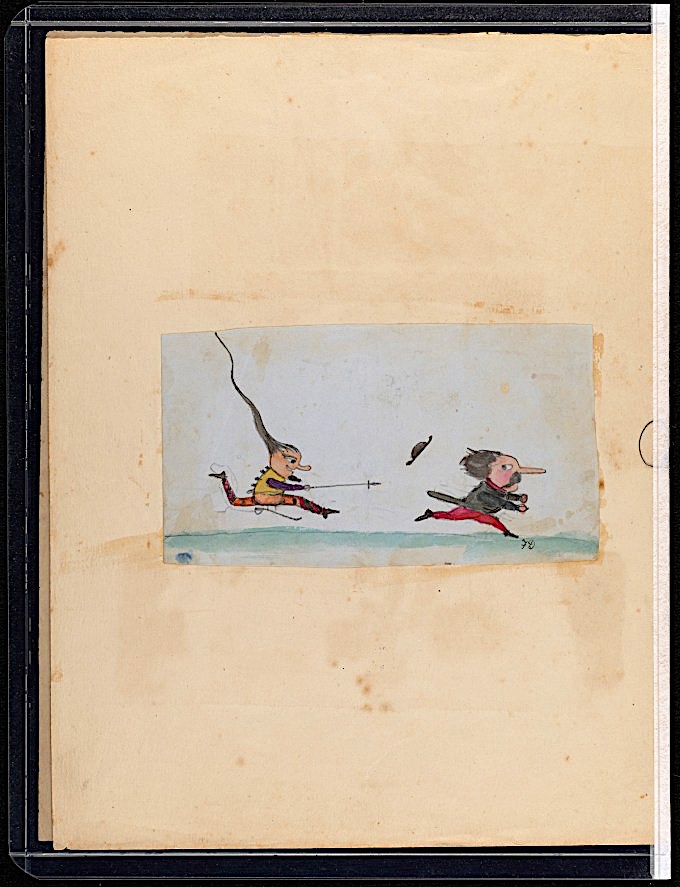

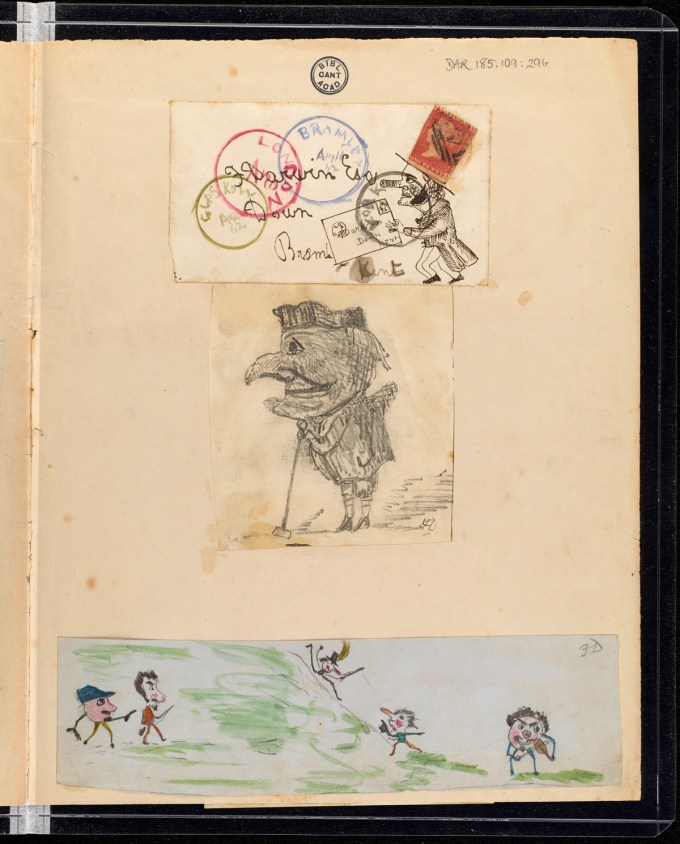

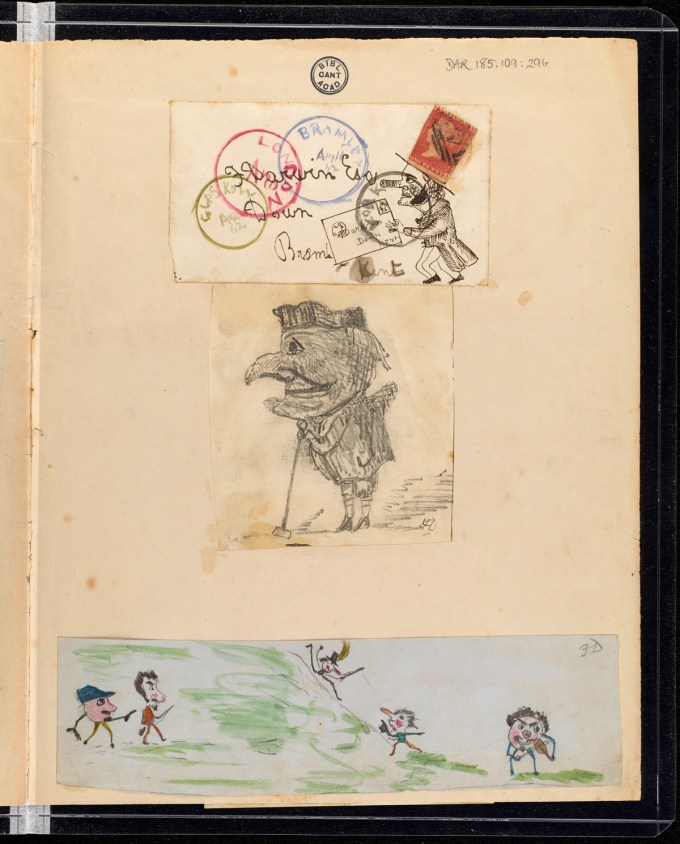

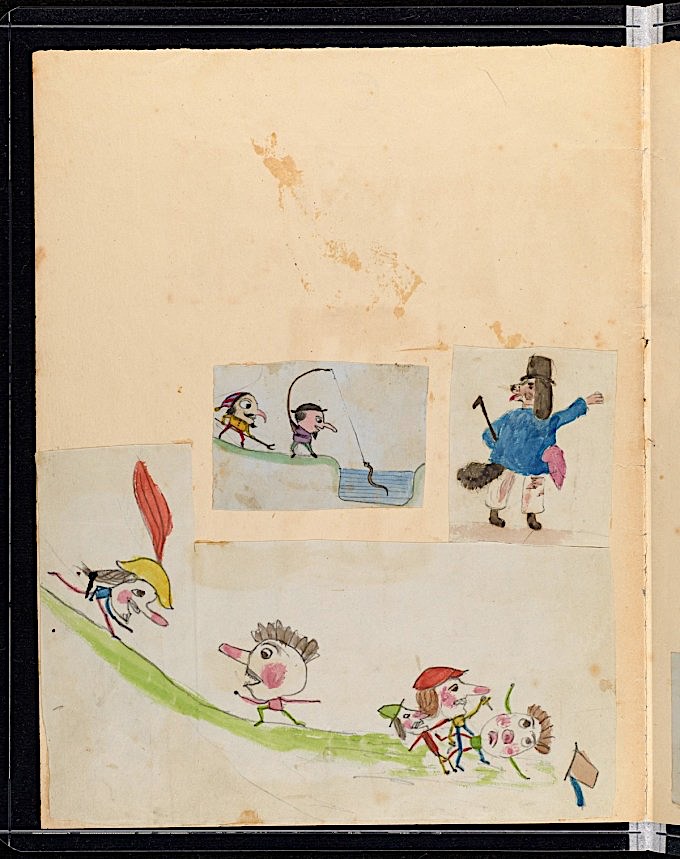

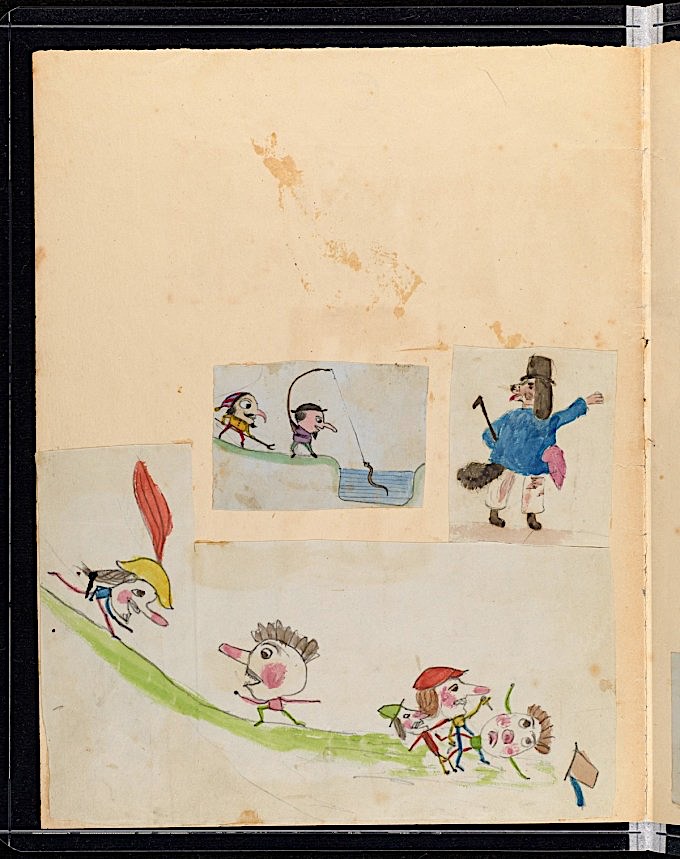

Down House was “by all accounts a boisterous place,” writes McKenna Staynor at The New Yorker, “with a wooden slide on the stairs and a rope swing on the first-floor landing.” Another archive of Darwin’s prodigious writing, Cambridge’s Darwin Manuscripts Project, gives us even more insight into his family life, with graphic evidence of the Darwin brood’s curiosity in the dozens of doodles and drawings they made in their father’s notebooks, including the original manuscript copy of his magnum opus.

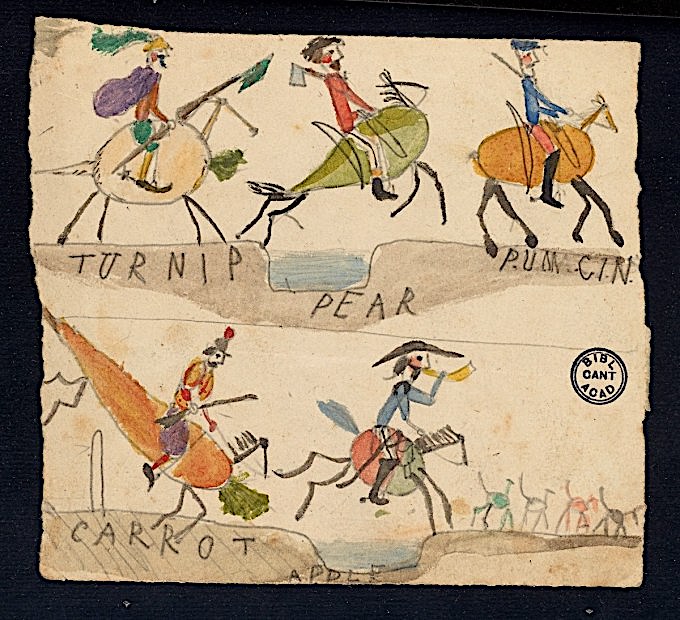

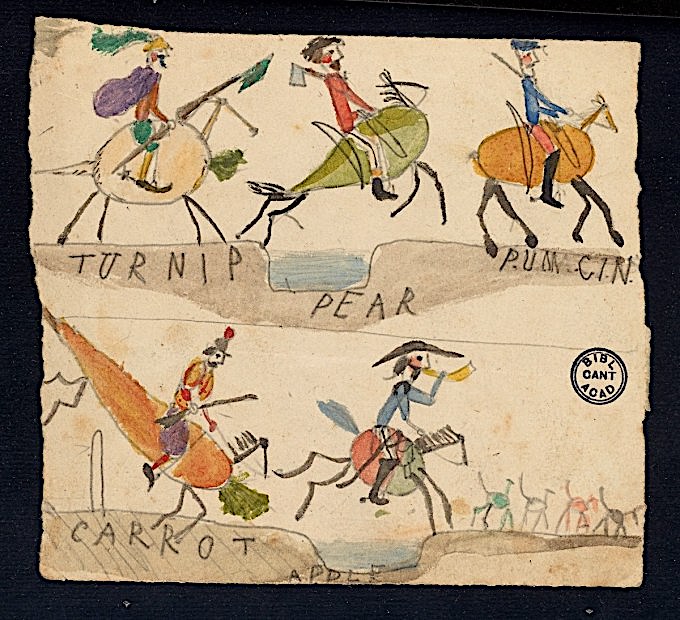

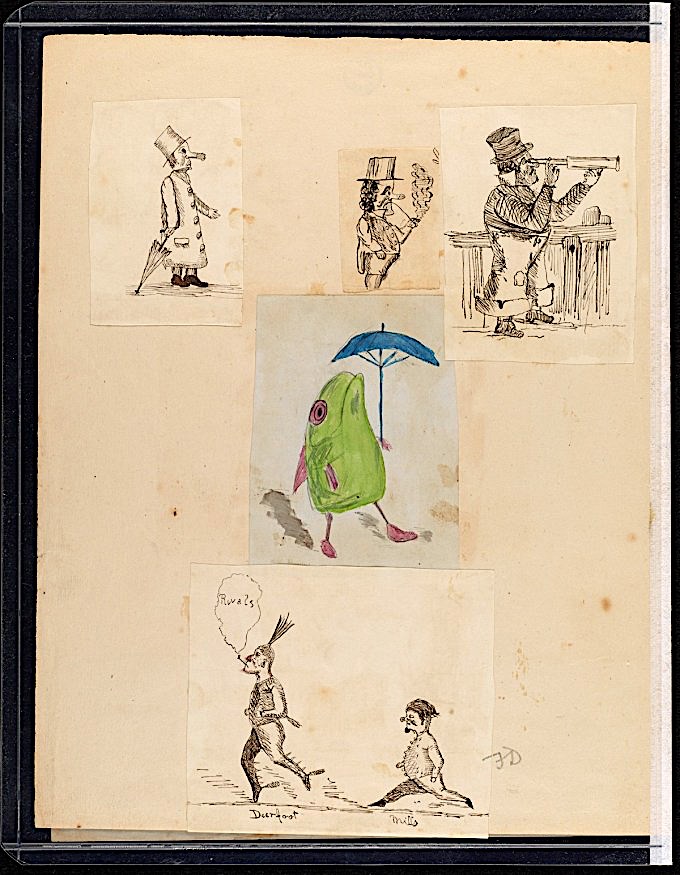

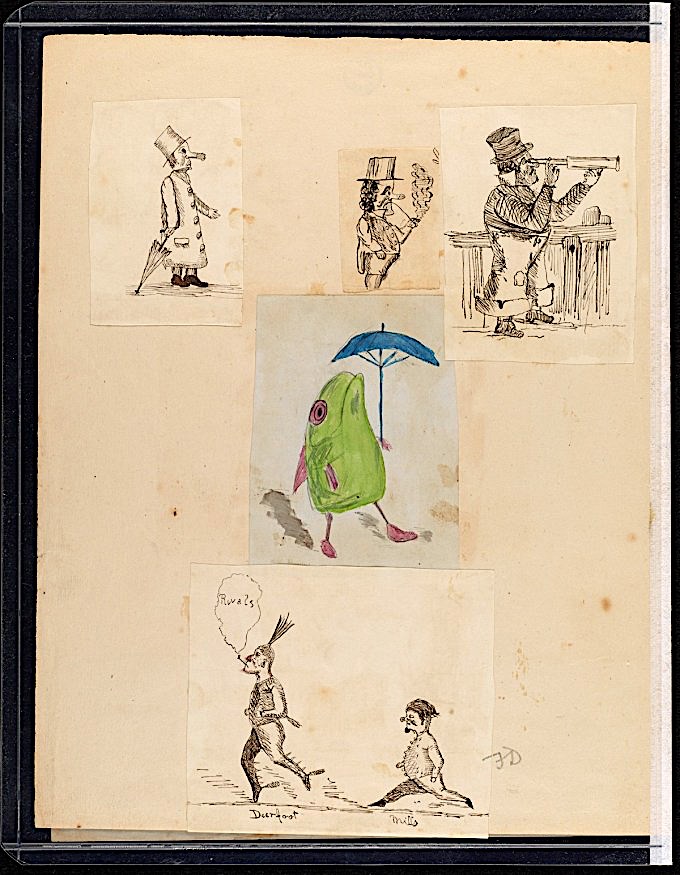

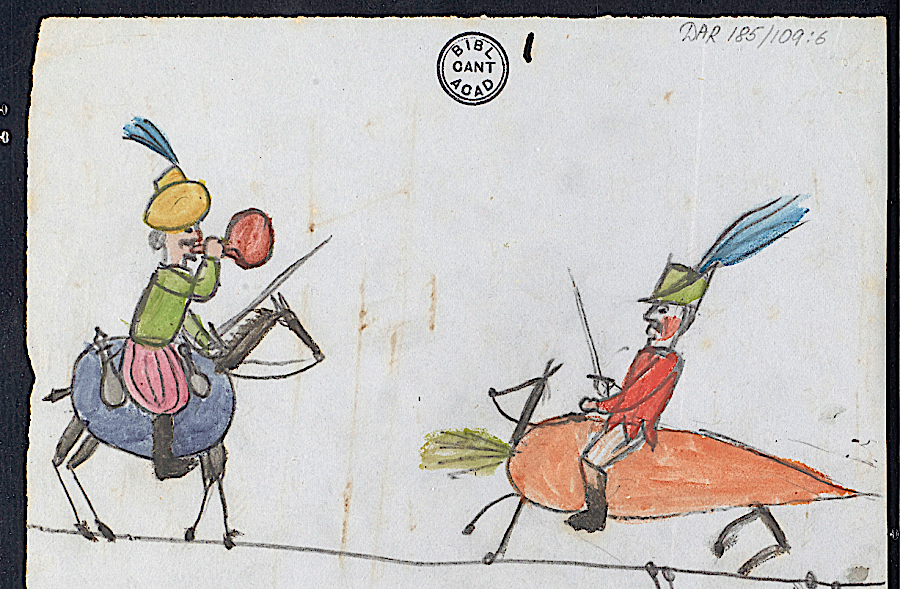

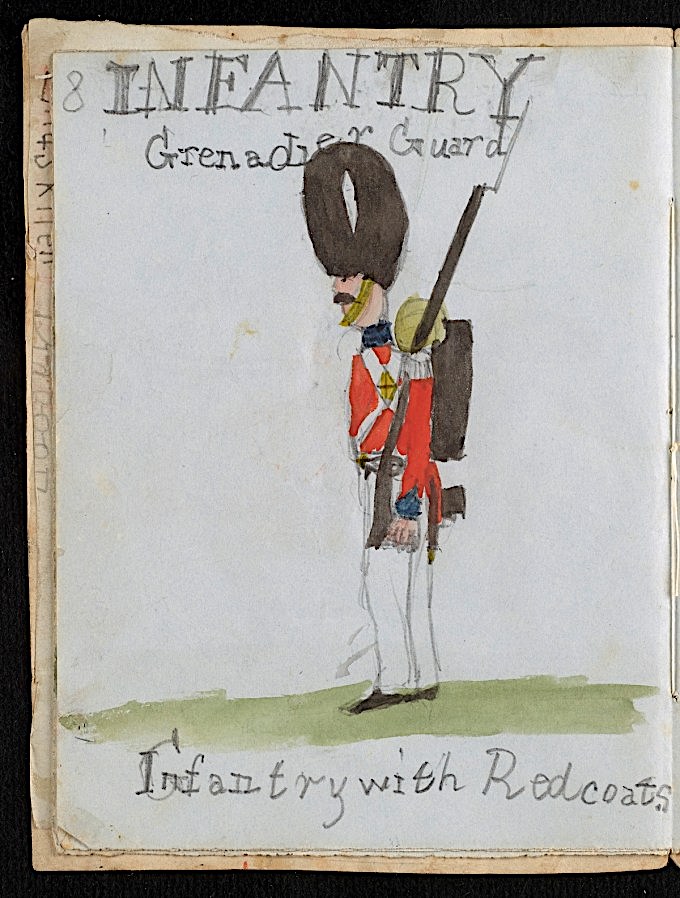

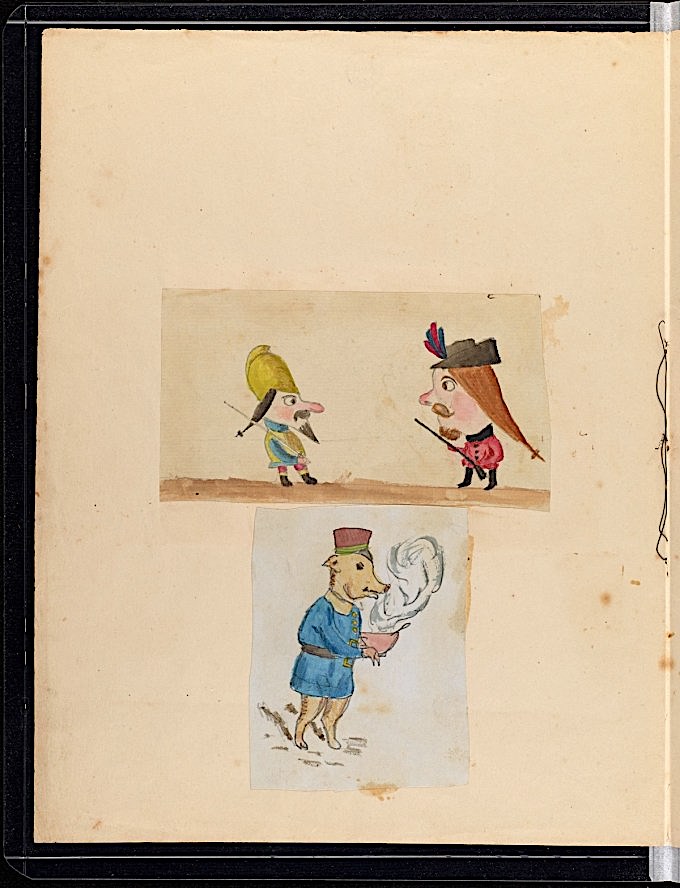

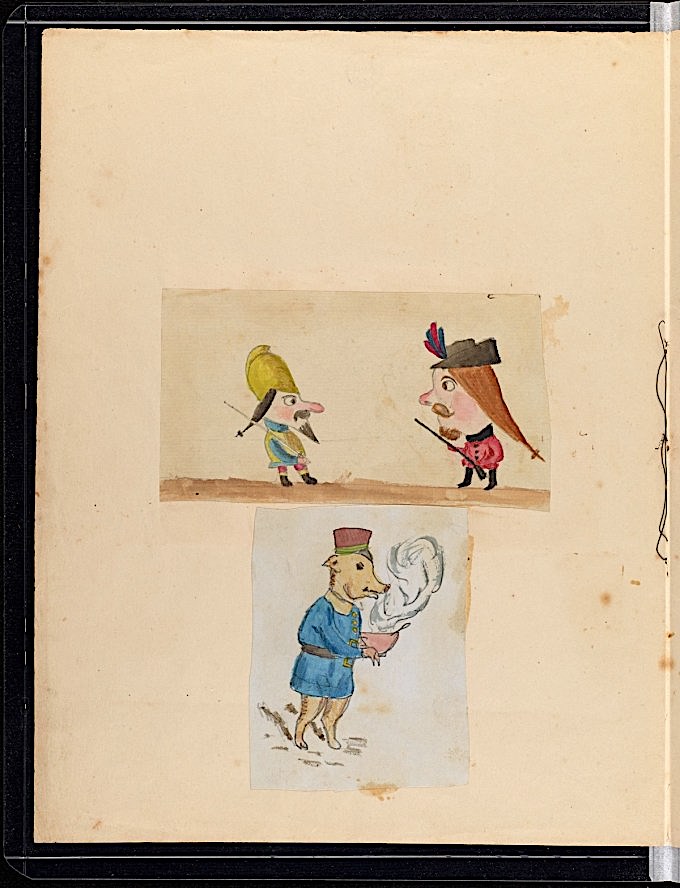

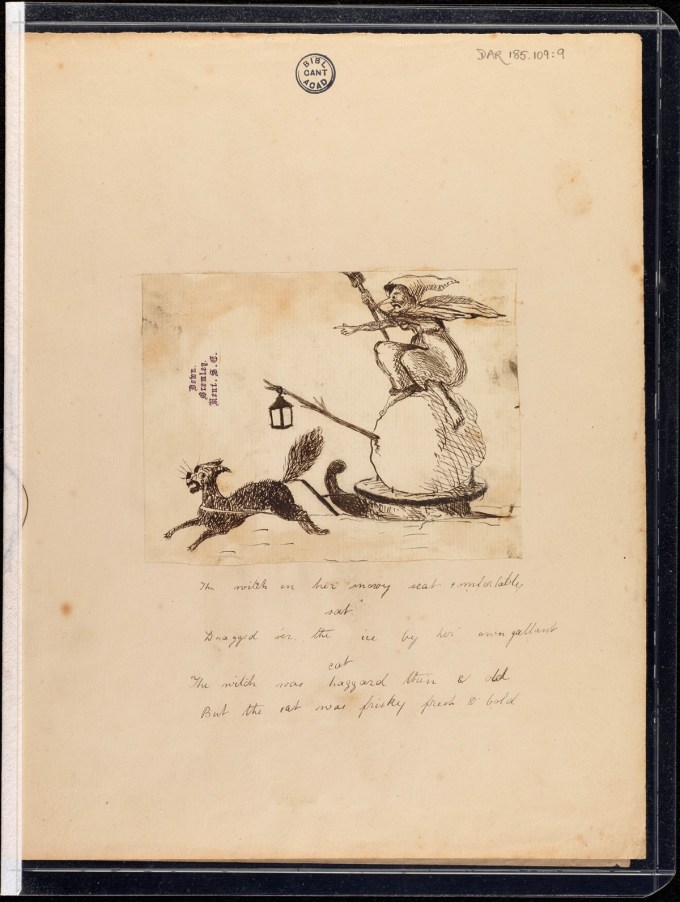

The project’s director, David Kohn, “doesn’t know for certain which kids were the artists,” notes Staynor, “but he guesses that at least three were involved: Francis, who became a botanist; George, who became an astronomer and mathematician; and Horace, who became an engineer.” One imagines competition among the Darwin children must have been fierce, but the drawings, “though exacting, are also playful.” One depicts “The Battle of Fruits and Vegetables.” Others show anthropomorphic animals and illustrate military figures.

There are short stories, like “The Fairies of the Mountain,” which “tells the tale of Polytax and Short Shanks, whose wings have been cut off by a ‘naughty fairy.’” Imagination and creativity clearly had a place in the Darwin home. The man himself, Maria Popova notes, felt significant ambivalence about fatherhood. “Children are one’s greatest happiness,” he once wrote, “but often & often a still greater misery. A man of science ought to have none.”

It was an attitude born of grief, but one, it seems, that did not breed aloofness. The Darwin kids “were used as volunteers,” says Kohn, “to collect butterflies, insects, and moths, and to make observations on plants in the fields around town.” Francis followed his father’s path and was the only Darwin to co-author a book with his father. Darwin’s daughter Henrietta became his editor, and he relied on her, he wrote, for “deep criticism” and “corrections of style.”

Despite his early fears for their genetic fitness, Darwin’s professional life became intimately bound to the successes of his children. The Darwin Manuscripts Project, which aims to digitize and make public around 90,000 pages from the Cambridge University Library’s Darwin collection will have a profound effect on how historians of science understand his impact. “The scope of the enterprise, of what we call evolutionary biology,” says Kohn, “is defined in these papers. He’s got his foot in the twentieth century.”

The archive also shows the development of Darwin’s equally important legacy as a parent who inspired a boundless scientific curiosity in his kids. See many more of the digitized Darwin children’s drawings at The Marginalian.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020.

Related Content:

16,000 Pages of Charles Darwin’s Writing on Evolution Now Digitized and Available Online

Hear Carl Sagan Artfully Refute a Creationist on a Talk Radio Show: “The Darwinian Concept of Evolution is Profoundly Verified”

Read the Original Letters Where Charles Darwin Worked Out His Theory of Evolution

Charles Darwin Creates a Handwritten List of Arguments for and Against Marriage (1838)