Courtesy of SFMoMA, San Francisco

Courtesy of SFMoMA, San FranciscoDismissed or trivialised by some as unserious and silly, Surrealist art was in fact largely born out of the brutal trauma of living under fascism, as these five striking works reveal.

It’s a century since André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism advocated a “mode of pure expression… dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason”. Writing was the intended vehicle for this unbridled imagination; art was thought too unspontaneous. Yet, just a year later, on 13 November 1925, the first exhibition of Surrealist art was staged in Paris, unleashing a world of peculiar, dream-infused works by artists such as Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray and Max Ernst.

VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2024/ Centre Pompidou

VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2024/ Centre PompidouGiven Surrealist art’s fantastic forms – from Salvador Dalí’s melting pocket watches and lobster telephone to Méret Oppenheim’s furry cup and saucer – it’s easy to dismiss or trivialise these outlandish works as more silly than serious. However, as galleries mark the Manifesto’s centenary with exhibitions on Surrealism and its legacy, the movement’s poignant response to the war years that spawned it is being brought to the fore.

The exhibition But live here? No thanks: Surrealism and Anti-fascism, at the Lenbachhaus in Munich, aims “to show that the movement of Surrealism formed at the same time as those fascist movements in Europe, and thus it is highly impactful and even constitutive, in many ways, of the political self-understanding of Surrealism”, co-curator Stephanie Weber tells the BBC. The Surrealists – with the exception of Dalí – were anti-fascist, often with close ties to the French Communist Party. “All the artists in our exhibition were personally impacted by fascism,” and “fought back”, says Weber. “Many of them were persecuted, they had to go into exile, they fought in the Resistance… and many of them either fell in war or were deported and killed.”

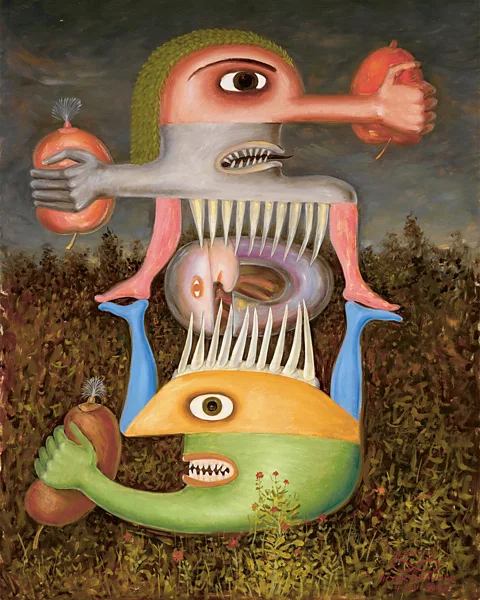

One of the featured artists is Romanian Jewish painter Victor Brauner. Faced with rising antisemitism, fanned by Romania’s Iron Guard, he made a new life in Paris in the 1930s, only to be displaced again in 1940 by the Nazi occupation. His oeuvre was nevertheless prolific, and conveys, says Weber, “this pictorial sense of humour” seen in Totem of Wounded Subjectivity II (1948), the exhibition’s flagship image. The oil painting features comical, cartoonish beings with arms for a nose or chin, but whose sharp teeth and spikes suggest menace. They clutch forms that evoke both fruit – a classic surrealist motif – and internal organs, hinting at something visceral and brutal. In the centre is the ubiquitous surrealist “egg”, a symbol of the ambition for a new reality, driven by the imagination and distinct from the suffering of the past.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/ Katherine Du Tiel/ Adagp, Paris, 2024

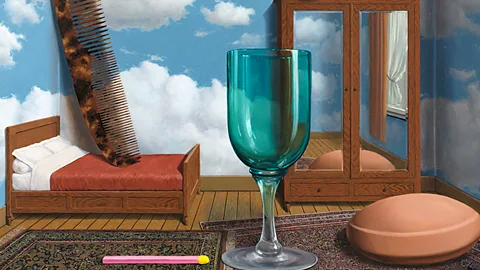

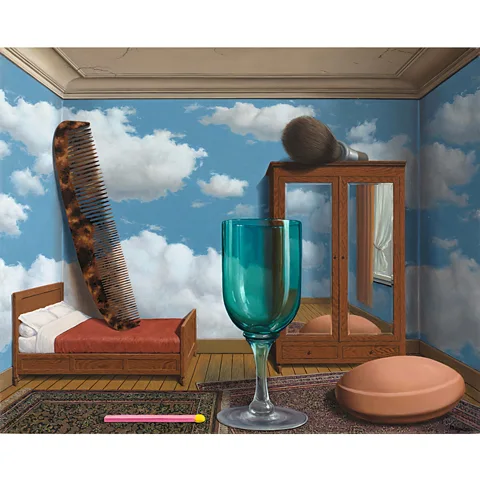

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/ Katherine Du Tiel/ Adagp, Paris, 2024In Paris, where Breton’s Manifesto was penned, visitors to the Pompidou Centre’s blockbuster exhibition Surrealism can now discover the original manuscript showcased at the heart of a labyrinthine journey through 40 years of mind-boggling art. The travelling exhibition began in Brussels, and will continue to Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia, but is currently at its most expansive, occupying a 2200-sq-m space. Highlights include René Magritte’s vertiginous Personal Values (1952), an absurd and amusing rendition of a seemingly small room containing vastly oversized everyday objects. This comedy, however, has suffering as its source. Disillusioned by the rational thinking that led to the mass destruction of world war, artists such as Magritte and his Dadaist predecessors embraced the illogical, creating disconcerting works inspired by the subconscious world of dreams.

Something monstrous

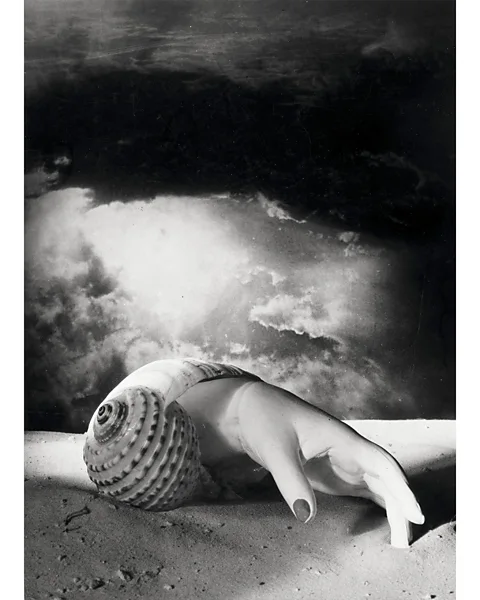

Though revolutionary in its vision, Breton’s manifesto was less progressive in its inherent sexism. Addressed to men, and written entirely from the perspective of the male experience, it fails to anticipate or acknowledge the crucial role women would play in shaping Surrealism. The Pompidou Centre pays homage to female artists such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and the photographer Dora Maar, frequently underestimated or dismissed as muses. The exhibition’s lineup includes Maar’s celebrated Hand-Shell (1934), an arresting image comprising two contrasting and incongruous objects: an elegant hand with a lone finger teasingly poking the sand, and the shell it emerges from – a reimagining, perhaps, of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. The work’s dramatic shadows and skies and its interwar context invite a range of readings, from the rise of a new world from the ruins of the past, to the imminent visitation of something monstrous.

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/ Dist RMN-GP/ Adagp, Paris, 2024

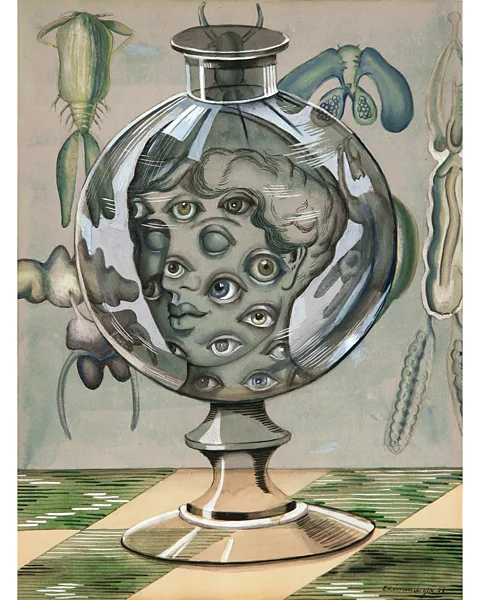

Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/ Dist RMN-GP/ Adagp, Paris, 2024This prophetic quality to Surrealism, drawn from the unconscious, is addressed early on in the exhibition where Edith Rimmington’s Museum, a “false collage” painting with a crystal ball-like centrepiece, commands attention. Tor Scott is researching this enigmatic British artist and is curatorial assistant at the National Galleries of Scotland, where a collection of Rimmington’s works and ephemera is held.

With its multiple roaming eyes, Museum “questions the balance of power between object and viewer”, she tells the BBC, and “speaks to the objectification of the female form”. The central feminine “artefact” is surrounded by floating sea creatures resembling disembodied female reproductive organs. Much of Rimmington’s output harnessed “visceral and violent imagery that would have spoken to those living in Britain during and after the interwar period”, says Scott. “Her work often included depictions of dismembered or mutated bodies and decaying flesh, as well as references to the cyclical nature of life and death.”

Murray Family Collection (UK & USA/ Chris Harrison / Estate of Edith Rimmington

Murray Family Collection (UK & USA/ Chris Harrison / Estate of Edith RimmingtonThis undercurrent of horror continues at The Traumatic Surreal at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, which explores female surrealists’ expression of the painful legacies of fascism. “Surrealism originates and is anchored in the trauma of war,” says co-curator Professor Patricia Allmer, professor of modern and contemporary art history at the University of Edinburgh, and the author of the 2022 book, The Traumatic Surreal: Germanophone Women Artists and Surrealism after the Second World War, that inspired the exhibition. “No male surrealist artist engaged as directly in representing and critiquing the Second World War as these women artists did,” she tells the BBC. Claude Cahun and her girlfriend Marcel Moore were incarcerated for publishing anti-Nazi propaganda, for example, and Lee Miller “really goes to war and photographs there. There’s not a single male Surrealist who does that”.

The focus of the exhibition, however, is Germanophone artists. “Either they lived under fascism or their parents were, in one way or another, involved in it,” says Allmer, stressing that the extreme patriarchal values that fascism embodied did not end with the war. “The whole ideology carried on but was kind of repressed and became this strange undercurrent.”

Courtesy of LEVY Gallery, Hamburg/Berlin

Courtesy of LEVY Gallery, Hamburg/BerlinOne of the exhibition’s most intriguing works is Squirrel by Méret Oppenheim, a German-born artist of Jewish heritage who fled with her family to Switzerland. Sculptures such as this fluffy-handled beer mug may seem humorous but are often “steeped in violence”, says Allmer. “On first impression, you have this lovely soft, bushy tail and it invites you to stroke it, and you’ve got the beer glass which suggests social pleasure and hedonism,” but the odd juxtaposition creates a shock effect “like a metaphor of the historical shocks of war experience that lead to trauma”. Implicit in the severed tail, says Allmer, is “cutting or amputating”, and its fur − a material also seen in the exhibition in the work of Ursula, Renate Bertlmann and Bady Minck – connotes something feral and frightening, the treatment of women as animals, and Hitler’s unsettling obsession with wolves. Black humour is deliberate and “a really important strategy”, explains Allmer, allowing women “to articulate realities that are otherwise repressed or excluded from public discourse”. Breton would devote an anthology to it in 1940, swiftly banned by the Vichy regime. Humour, he writes, is “the process that allows one to brush reality aside when it gets too distressing”. If we find Surrealism funny, we’re not necessarily missing the point.

Surrealism is at the Pompidou Centre in Paris until 13 January 2025.